Gabrielino/Tongva Nation of the Greater Los Angeles Basin

a.k.a. The Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe

106 ½ Judge John Aiso St #231

Los Angeles CA 90012

(951) 807-0479

http://www.gabrielino-tongva.com

Welcome

Since time immemorial, we the Tongva People have inhabited the 4,000+ square mile region we call Tovangar, known today as the Greater Los Angeles Basin. Our natural, ancestral boundaries are from the Santa Susanna Mountains to the North, Aliso Creek to the South, the San Bernardino Mountains to the East, and the Pacific Ocean to the West, including the four channel islands of Santa Catalina, San Clemente, Santa Barbara, and San Nicolas.

Los Angeles skyline.

It was October 8, 1542, when Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo noted in his log his description of the “Bay of Smokes” (San Pedro Bay). Over two hundred years later, on August 2, 1769, Captain Gaspar de Portolá and his contingent of men, camped in Yaang’na (Los Angeles). Both groups encountered the Tongva People living in the respective areas.

In 1771, the Spanish turned their sights to conquer and enslave the Tongva by using them as the slave labor force to build the Misión de San Gabriel Arcángel, giving the Tongva slaves the name of Gabrieleño.

In the name of the king and queen of Spain and of the Pope, disease, rape, kidnapping, enslavement, imprisonment, and slaughter by any means followed the soldiers of Spain through the territory, starting with the rape of the wife of a chief, the murder of the same chief as he confronted the soldiers at the mission, and the enslavement of the chief’s son through baptism making the son a ward to the church when his mother tried to appease the friars to bring peace to all. The friars took this as a sign to start the forced relocations in earnest.

In 1824, Mexico became independent, their constitution guaranteeing citizenship to all people, giving Natives the right to live free in their villages. The Colonization Act of 1824 gave land grants to white Californians and well connected citizens of Mexico. By 1834, Mexico’s intent for secularization of the missions to remove the authority of the Franciscan missionaries, had little effect on the conditions and quality of life for the Tongva, as the authorities took the land for themselves. In essence, Mexico removed the master of the church and replaced it with the masters of the rancho. Ten years had passed, with the citizens of Mexico treating the Tongva and other Natives as slaves once again. In 1846, Mexico’s government called for the locating and destroying of native villages.

On April 22, 1850, the California State Legislature passed the Government and Protection of Indians Act (Chapter 133, Statutes of California, April 22, 1850) taking the rights away from the Natives that the government of Mexico had given them. This law was further amended and approved on April 18, 1860, effectively hiding their intent to enslave the Natives by passing a law for indentured servitude and therefore gaining acceptance as the 31st state during the time leading up to the Civil War of the United States.

The 1.2 million acres promised to the Gabrielino Tongva People never happened due to the disease called “Manifest Destiny” that was racing through their territory. Edward Beale, an Indian Affairs Superintendent, stole the 50,000 acres near Fort Tejon and the cattle delivered there, from the Natives he was overseeing, by incorporating the land into the Fort Tejon Ranch as the owner, making him a rich man and using the Natives as forced labor. The Natives included the Gabrielino Tongva People.

In 1892, Sherman Indian School was founded in Perris, California and then moved permanently to Riverside, California in 1910. This school’s mission at the time was to assimilate the children of the local tribes into “white society.” The students were forced to work long hours and face corporal punishment, while not being able to see their families or participate in their respective cultures and heritage. The Gabrielino Tongva children were no exception to this.

In 1905, the “18 lost treaties” of 1851 and 1852, set aside 8.5 million acres of land for reservations in California and were to be signed by President Fillmore, were discovered hidden in a secret compartment in a desk drawer in the Senate Archives.

The California Indian Judgement Act of 1928-1933, tried to make up for the failure to enact the treaties of 1851 and 1852 by paying $0.07 an acre, minus expenses and divided between all the approved Native applicants for the census roll.

This continued with the census in 1948-1950 and with the census in 1968-1972, as the U.S. government tried to remedy what their actions had caused. The Tongva were included in all three censuses under the name Gabrielino, but are still to this day unrecognized by the federal government, though we have contributed greatly to the founding of California and are repeatedly acknowledged through other federal government means on an individual basis.

To this day, we are not allowed to claim and repatriate our ancestors’ remains. We are not allowed to participate in the scholarships for Native Americans. We are not allowed to sell our traditional crafts and wares as Native Americans without facing the same $250,000 fine and 5 years imprisonment as any others that appropriate Native Culture for monetary gain. Some are not allowed to seek health care at the Indian Clinics.

Yet, we are still here, as we have been since the beginning. We are part of this land. We will remain. We will endure, because we are Tongva.

Pictographs in the Santa Susanna Mountains. A site used by the Tongva, the Tatavium, and the Chumash.

Pictographs in the Santa Susanna Mountains. A site used by the Tongva, the Tatavium, and the Chumash.

Stone pot recovered and rescued near Kuruvungna, a scared site and village located at University Senior High School (West Los Angeles).

Stone tools recovered and rescued in Passinonga (Chino Hills).

Horuuvngna village site in Jurupa. This was a place for food preparation. The smooth indent is used for grinding acorns.

Mortar and pestle used for grinding food.

Narcisa Higuera (future Mrs. James Rosemyre) and family. In 1905, she recorded Tongva language and Tongva songs for C. Hart Merriam.

Tongva child Joe “Chemo” Valenzuela was about ten years of age when he appeared in “The Mission Play”. This was the first play of The San Gabriel Mission Playhouse. President Coolidge attended one of the showings.

Honoring our Elder Guadalupe Simental at La Plaza de Cultura y Artes in Yaangna (Los Angeles).

Honoring our Elder Guadalupe Simental at La Plaza de Cultura y Artes in Yaangna (Los Angeles).

Honoring our Elder and WWII Veteran John White at La Plaza de Cultura y Artes in Yaangna (Los Angeles).

Presenting the Gabrielino/Tongva Nation Flag for the first time – December 8, 2012, Chokishngna (El Monte).

Presenting the Gabrielino/Tongva Nation Flag for the first time – December 8, 2012, Chokishngna (El Monte).

irginia Carmelo in traditional regalia singing at Moompetum at the Long Beach Aquarium.

Teaching tradition in Passinonga (Chino Hills).

Swearing in returning Tribal Council Members in Yaangna (Los Angeles).

Swearing in the Election Board in Riverside.

Tongva Annual Fishing Day at Shevaanga (Whittier/Whittier Narrows North Lake).

Teaching the next generation to fish during the Tongva Annual Fishing Day at Shevaanga (Whittier/Whittier Narrows North Lake).

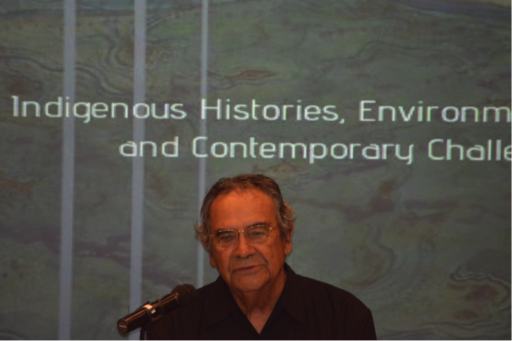

Elder Edgar Perez speaking at Loyola Marymount.

Our “Day in Court” – Superior Court of the State of California Case No. BC 361307 – Yaangna (Los Angeles).